A long time ago, I was at Living TV when they held an open audition for psychic mediums. More specifically to find one psychic medium who would be the star of a new show. The queue was very long and there were hundreds of applicants. What was striking was the confidence that each of them had that they would be chosen. Given that predicting the future is what psychic mediums are supposed to be able to do, it kind of made sense.

Now what struck me was that most of them would turn out to have made the wrong prediction. They’d foreseen that they’d get the job but instead someone else would. Clearly a sign that they weren’t such good psychics.

But one of them would be vindicated by virtue of winning the role, which would show that their powers of prediction where accurate. In a 500-1 gamble they alone had got it right. Which would be the proof that the selection process had worked, Living TV had found a medium who could see into the future . . .

—–

This is a true story but the logic in it is of course flawed. It’s a self-fulfilling prophecy – whichever applicant won the role would by virtue of being chosen have their predictive “abilities” vindicated. Instead they would just have been lucky. But viewers might draw the conclusion that this example of luck was evidence of their ability to get lucky again in the future. This rationalisation is what psychologists call Epistemological Luck.

The idea of Epistemological Luck is that if someone makes a chance call right once, we believe that they’re more likely to be able to do it again in the future. If I correctly guess a coin toss once am I more likely to guess right the second time? And the third. And the fourth? The truth is that if I guessed right four times you might well think I had a more than 50:50 chance of getting it right a fifth.

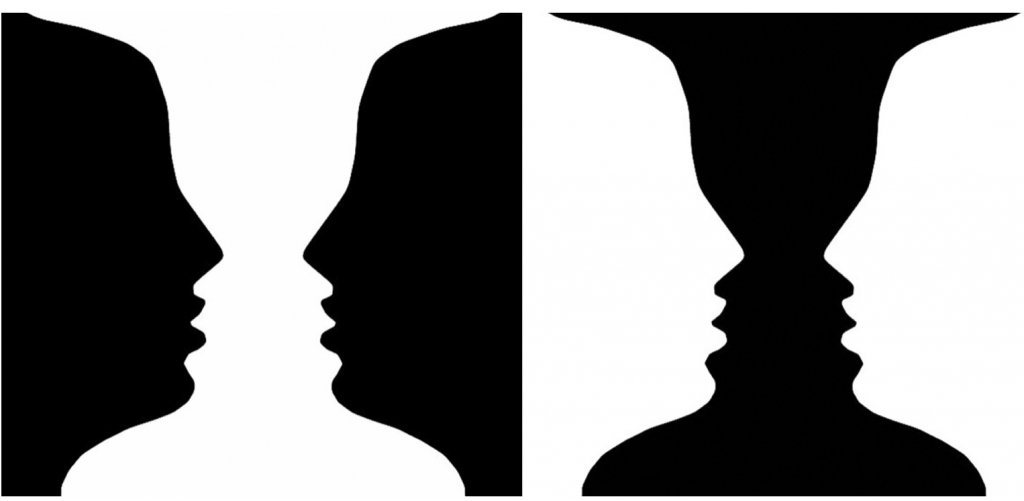

This is a function of how we try to make sense of the world, by seeing order and patterns in it. This famous Gestalt theory drawing from Edgar Ruby is an example of how we’re drawn to find meaningful patterns (in this case of course there are two).

What we’re often doing though is rationalising intuition, or emotion. Something feels like it has a logic so we create a reasonable sounding story to explain it. In other words, we’re kidding ourselves (by the way, this is what magicians have used to create tricks of the mind throughout human history).

This is also why reason tends to be biased in favour of what we already believe. Although reason and rational argument are vital to problem solving and making the right decisions, more and more evidence shows that we often have the cart and the horse the wrong way round. In The Enigma of Reason, the psychologists Hugo Mercier and Dan Sperber explore how human language and reason evolved as ways of convincing others in the group to agree with you. This persuasive mode has then further evolved as a way of problem solving and iterating ideas, but it’s useful to know that we have a natural pull to use reason to win an argument, more so than to find the right answer.

It can be very useful but also sometimes very hard to separate these two strands in our thinking. Is the case I’m making to myself a rationalisation of something I emotionally want to believe, or an objective analysis?

In coaching we often work with clients to separately identify the constituent parts of their thinking and by talking out loud to develop a greater sense of objectivity. Moreover, by being coached over time, looking at a variety of different issues or problems, new habits of mind can develop and be strengthened.